Jason Forbes

Disability Advocate

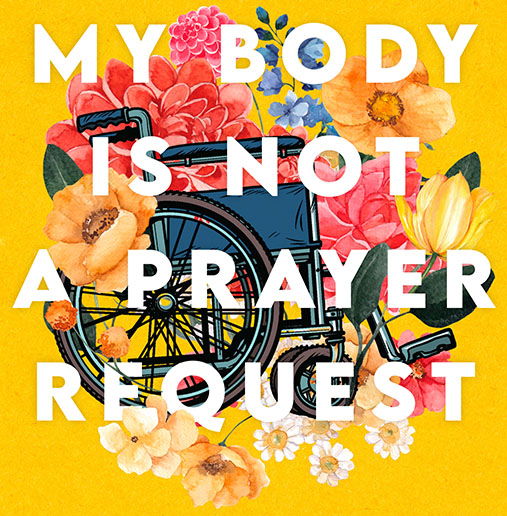

My Body Is Not a Prayer Request: Disability Justice in the Church.

Dr. Amy Kenny. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2022. 208 pp.

In her book My Body is Not a Prayer Request: Disability Justice and the Church, Amy Kenny presents a candid and confronting account of her life experience with disability. The concern of the book is to identify the impact of ableism on people with disabilities and its pervasiveness in the church and culture. Kenny defines ableism as “the belief that disabled people are less valuable or less human than our nondisabled counterparts” (p.15). As Kenny demonstrates in her book ableism manifests itself in the design of public spaces, attitudes, and language.

Ableism

“…the belief that disabled people are less valuable or less human than our nondisabled counterparts.”

Amy Kenny, p. 15.

Kenny begins her book by discussing how ableism is felt in the church. In this case, it’s people seeing her as an opportunity to pray for healing. She explains that such perceptions are undergirded by ableism. Kenny refers to such people as “prayer predators.” Instead of being freed from her disability, Kenny argues that what we all need to be freed from is ableism.

Kenny’s experience therefore becomes the basis for her book. From this experience comes discussions around discrimination from the education system, the medical profession and the church; attempts to downplay her disability by the general public and government departments; the dehumanising treatment of her by medical professionals; the blessings that come with disability; the importance of language; the lessons that can be learned from life with disability; views around the eschaton; and the importance that including people with disabilities has for the church.

Perhaps the clearest example of abelist assumptions creeping into the church is in chapter 9 where Kenny discusses how views of eschatology has implications for relating to people with disabilities. While the notion of no “disabilities in heaven” may seem like cause for hope, such thinking carries the assumption that people with disabilities a less whole than people without disabilities, and they must be “fixed”. As Kenny points out, she does not know anyone who has been the subject of prayers for healing or calls for repentance simply because they wear glasses (p. 171). Instead of seeing her life as something less whole, Kenny draws attention to the liberties that people with disabilities often enjoy, especially through assistive technologies. While there are losses associated with living with disability, there are also gains. Understood this way, disability can be perceived as part of the diversity that God has instilled in his creation. This also includes how time is managed and what one does with their time. Kenny finds encouragement in the idea that God relates to time differently to most people. Therefore, there should not be any pressure to conform to the time-constrained routines that most people follow. Finally, there is encouragement in the while crucifixion is something shameful, for those who follow Christ it has become the basis of hope – something to boast in (Gal 6:14). This provides a basis for seeing disability as something to give thanks for rather than to be ashamed of.

Kenny has provided a comprehensive insight into her life with disability. Her personal frustration with the attitude of the church and the medical profession can be felt throughout the book. This is what gives the book is thrust, while at the same time it can make the book difficult to read. Personally, as someone who lives with disability, I found the book “triggering” at times, and needed a break from reading. What would have helped Kenny’s presentation is some chronological context. When recounting her experiences, Kenny jumps back and forth between her experiences as a young child, a teenager, and an adult. It’s not always obvious which period she is reflecting on. While attitudes towards people with disabilities still have a long way to go, they have already come a long way, and can vary from region to region. This is not greatly recognised in the book. Ecclesiastical context would have also helped her presentation. The experience that Kenny has had in the church is not reflective traditions.

Even with these limitations, Kenny has produced a book that challenges how the church thinks about disability and confronts the church over allowing ableism to seep into the church. For this reason, I commend her book.